Thank you Debra Martens for hosting me and my dear friend and colleague, Anna Levine, on your site today. It was a pleasure.

Working in silence, alone with your thoughts, writing can be a lonely business. But have you looked at the list of acknowledgements at the back of some books lately? They seem to be getting longer, as if a book has become the child raised by a village. Does anyone work in isolation? Some writers try groups, some rely on editors, and some have writing partners. In "Someone to Read Your Drafts," a chapter of Bird by Bird, Anne Lamott concludes: "Almost every writer I've ever known has been able to find someone who could be both a friend and critic." (Bird by Bird, First Anchor Books 1995, p. 170.)

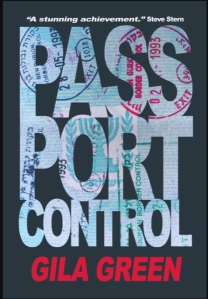

I found not one but two Canadian authors working here in Jerusalem. After getting her Bachelor of Journalism degree, Gila Green left Ottawa in 1994 for Israel, which was a halfway point between Canada and South Africa (her husband couldn't come to Canada and she couldn't work in South Africa). Anna Yaphe Levine left Montreal when she was 20 and did an MA in English Literature at Hebrew University. Both stayed in Jerusalem, both have children, both have made homes in various countries, both teach, and both write for young readers (a first for Green with her forthcoming No Entry). They met in a writers' group but soon found a better fit working together. I asked how it works, this writing partner thing. Here they are in conversation. (Details of their publications and awards appear at the end.) We begin with Gila Green making the introduction. -DM

Gila Green: I had to fly from Israel to Montreal to find my critique partner. To be precise, I had to fly to a writer's workshop in Montreal, to meet an American who knew an ex-Montrealer living in Israel who asked me in her native New York accent, "You don't know Anna Levine? She's Canadian, too."

At that time my answer was "No," with a dash of subtext: not interested. I had tried several critique partners and all of them flopped. Unreliability was inescapable; then there are the ones who love everything, really need a mentor, edit your work as if it's their own; did I mention unreliable?

By the time I flew to Montreal I had put a writing partner in the category of trying to sneeze with your eyes open — i.e., it can't be done. It was just another: what do I expect living in Israel? How many English-speakers could I possibly have to choose from?

Enter Anna Levine. Her critiques were enormously helpful right away. And I'd finally found someone as obsessed, relentless, and reliable as I was. We have different strengths, which is hugely important.

Anna Levine: After returning to Israel following three years in California, where I started writing children's literature and worked with two other well-published writers, I was desperate to recreate a strong writing group. I knew what I wanted, writers who wrote as well as they could critique. At one time I found myself juggling five different writing groups. Like Goldilocks, I was looking for the one that fit just right. When Gila and I met, we were in a writing group with three other women. When that group fell apart, we continued to meet on our own, realizing that we'd found the right fit.

Green: So how do we work together? First of all we don't apply pressure. Second of all we pressure big time.

Levine: Having a deadline works. We set a date when we plan to meet, then a couple of weeks prior to the meeting, we send each other our work by email. This gives us time to critique. What usually follows is a few furious WhatsApp exchanges, often ending with, "Do you think we have time to add another chapter before our meeting?" This is important, because when I write the new chapter it's with the changes that Gila suggested still fresh in my mind. Her comments drive me to write forward.

Green: On the other hand, we both know when to back off. If one of us is in a marketing phase or just a too-overwhelmed-with-life zone, the pressure disappears with no time limit. It can be three months or nine, if it's not writing-critique time then we wait until the cycle rolls around again guilt-free. We both have back-up critique partners to fill in the gaps and there's no residual hard feelings, which I think means that a key element in our relationship, the foundation underneath, is built on respect.

Levine: We've all heard the old adage — keep your day job. Both Gila and I have family obligations as well as a day-job work load. Understanding that our writing goes in cycles (often set to the calendar of school vacations and Jewish holidays) lets us be in sync. That's a big one in a writer's group. One group I'd been working with I had to leave because we met twice a month. On one hand that sounds like a dream; in truth, I spent a lot of time reading other people's work and found no time to work on my own writing. I still meet with another group and do manuscript exchanges with individual writers. Finding the right group doesn't only mean the right people, but the right schedule that leaves time for your own writing, while giving the other writers you're working with the attention their manuscripts deserve.

Green: When we are critiquing each other's work, I know my ideas are respected, which shouldn't be confused with admired — rather, weighed with seriousness. I can display the first three chapters of a new work on the table between us and when Anna takes out her red teacher's pen, flips to chapter four and says: your book really starts here, I know she identifies with how that feels and cares enough to tell me anyway.

Levine: We all start with what Anne Lamott beautifully describes as that shitty first draft. And yet, when I'm writing that first chapter I'm sure it's a keeper. Theoretically, I know that those first chapters and sentences are the writer's way of feeling oneself into the story. It's your critique partner's job to say, the story works, now get to where it really begins. Though Gila and I have been working together for many years, it took a few first chapters until we figured out we could be honest without being discouraging or disrespectful. When you begin working with a new group of people, you have to be careful not to make rash judgments.

Green: Negotiating the pitfalls of being too familiar with a style/voice is an issue but there are ways around it. Time helps. We have long breaks where we don't read each other's work. I'm careful not to let Anna over critique my work. If I feel she's given her all to my piece, I whisk it away. She's never read my final drafts. The plus side is that I know when she can do better.

Levine: One of the hardest things for me is taking that step away from my work, letting it sit so that when I come back to it I see it with new eyes. Not overworking a piece is important. While there's a disadvantage in being too familiar with your critique partner's voice, the advantage is that you know when her character's voice rings true. You are more attuned to inconsistencies and can tell yourself that it doesn't sound like she'd say this.

Green: In conclusion, I get more done with a writing partner, not less. I keep perspective. No one partner can be all things at all times. As long as they're around at crunch time, which for me is first draft time, it works. With a fellow expatriate Canadian, there's no time wasted in explaining my Canadian-ness or the feeling of otherness that all expats go through. The two of us work very differently, which is probably why we match so well. We have great fun at our sessions and I always come away with something valuable that remains in my work in its final form — to a writer that's worth gold and cannot be taken for granted.

Levine: It is ironic that I've gone half-way around the world to find a critique partner who lived two hours from my home in Montreal. We both have a Canadian sense of time (we're punctual), and work ethic (we show up) and though we spend the first few minutes of the meeting catching up on family stories, we quickly get down to the nitty gritty. It's familiar. It's professional. It's fun and it works!