Author Interview: Ann Bausum

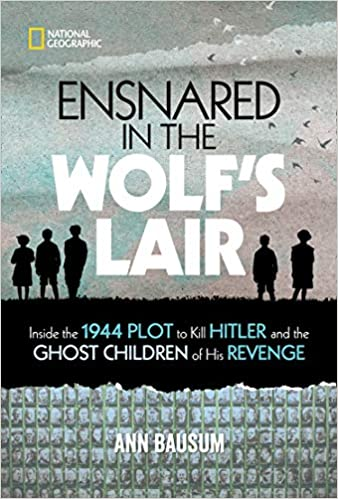

Ann Bausum is an award-winning author of 16 works of nonfiction for children, teens, and adults. Her books often explore under-told stories and examine social justice history, but she's also written twice about a famous dog! Earlier this year National Geographic published her latest book for middle graders and up: Ensnared in the Wolf's Lair—Inside the 1944 Plot to Kill Hitler and the Ghost Children of His Revenge.

"I hoped that my book could offer a fresh example of Hitler's insatiable quest for revenge."

by Ann Bausum

I am so happy to welcome Ann Bausum to gilagreenwrites today. History is one of my favorite subjects, something we share. I wish to congratulate her on her new and important book. Welcome Ann!

GG: How did you begin your research for this book?

AB: In 2015 I visited Europe in search of a story at the encouragement of National Geographic Kids. Among my destinations was the remains of the Wolfsschanze, or Wolf's Lair, one of the command posts built for Adolf Hitler's use during World War II. History related to this remote site in Poland had caught my publisher's eye, and I wanted to see the place for myself. Although I ultimately chose a different angle for Ensnared in the Wolf's Lair, memories from my snowy visit to this otherworldly site remained vivid while ideas incubated for the book.

In 2018, after the Trump administration began forcibly separating children from their parents at the southern U.S. border, my mind jumped to the 1944 family separations instituted on Hitler's orders after the failed Valkyrie attempt on his life at the Wolf's Lair. This little-known episode helps to illustrate Hitler's insatiable pursuit of revenge through all layers of society. Many of the conspirators who had tried to assassinate him and overthrow his regime came from the surviving families of the former Imperial reign. Hitler was infuriated and invoked the Sippenhaft policy of collective family punishment for the clans involved.

Later that year I returned to Germany so that I could visit specific sites related to this history—and interview eyewitnesses to these family separations. Among those who were kind enough to speak with me was Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, the eldest son of Hitler's would-be assassin, Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg.

GG: What was your goal in writing this book? Do you have a particular connection to it?

AB: I hoped that my book could offer a fresh example of Hitler's insatiable quest for revenge. I found it telling that his focus and that of his deputies could be so relentless during a time when the regime faced attacks on all fronts. And yet still officials kept tabs on the locations and confinements of multiple surviving family members. The hastily conceived detentions—which may have been intended initially to end with murder for all but the youngest of children—morphed into a complicated subterfuge. Heinrich Himmler managed the logistics personally, seemingly with the intention of using these high-profile families as pawns in his effort to avoid his own post-war punishment.

Although I bring no personal connection to this history, I did build meaningful bonds with several of the eyewitnesses to history. Our conversations and correspondence added depth and emotional weight to my work. I remain grateful for the stories they shared with me.

GG: What do you think about the proliferation of comparing just about any injustice that happens today with the Holocaust/Nazis/Hitler? Do you think this is justified?

AB: Although such direct comparisons may be called for at times, we might do well to reiterate the history itself in a way that empowers people with the tools and facts to intuit their own insights into parallels and repeating patterns. I chose this more organic approach with Ensnared in the Wolf's Lair. For example, the first chapter of the book outlines how Hitler exploited the democratic process to seize power and become a dictator. Readers are left to make their own comparisons with other political periods and figures, but, with Hitler's example as a reference, they may be better able to see how demagogues can become dictators.

GG: What is the significance of the title?

AB: Although the Wolf's Lair is literally a significant place name in the story, it also serves as a metaphor for the Nazi regime itself. In various ways the historical figures I write about find themselves ensnared by Hitler and his network of cronies and accomplices. Some are literally caught up in the show trials and executions that follow the assassination attempt at the Wolf's Lair and the wider failed coup beyond it. Others are ensnared in the Gestapo apparatus of punishment that subjects family members to arrest, extra-judicial detentions, and the accompanying terror caused by the uncertainty of their situations.

GG: What is your reaction to those who talk about "Holocaust fatigue" when it comes to books? Can we have too many books about Hitler?

AB: Ideally new books should offer fresh insights so that readers instead of feeling fatigued or desensitized are stirred to gain new insights into a time that is slipping beyond our lived experience. I sense that we turn to this history as a reminder of how encounters with the worst instincts in the human family can inspire us to find the strength and moral courage to respond with our best.

GG: Would you like to add something?

AB: During my research I was particularly stuck with how successfully the Nazi regime weaponized terror on every scale—from the horrors of the Holocaust to the everyday fears that emerged from living a state of constant uncertainty.

I found it striking that so many of the conspirators who turned against Hitler shared the same tipping point—their personal revulsion upon witnessing or else hearing about the regime's systematic murdering of civilians on the Eastern front and through Nazi death camps. Some conspirators had opposed Hitler from the beginning, but many had been indifferent or even supportive during his rise to power. One epiphany at a time they were moved to use their skills and influence to try and topple his regime.

I had not previously appreciated the difficulties this group faced while trying to implement its objective—it goes back to that web of ensnarement—and how trapped people had become within the dictatorship. It took months or more to knit together a counter web of trusted accomplices, and more time still for one of them to gain access to the reclusive Hitler. Yet even as they were putting their plans into place they knew that, should they fail, their actions would compromise not just their own lives but the safety of their family members.

Which brings us back to the power of terror.

After the conspiracy collapsed, family members caught up in Hitler's post-Valkyrie revenge never knew what could happen next. Children separated from their older relatives slept in well-made beds and ate three meals a day, but from one day to the next they didn't know if they would be among those permitted to leave—or if they would ever see their families again. Likewise, their older relatives might find themselves moved from jail cells, to hotels, to prison quarters at concentration camps, then back to hotels with no rhyme or reason. Freedom—or death—could follow at any moment.

Their experiences cannot compare to those of the people swept up by the Holocaust, but even on this small scale the regime kept its prisoners ensnared. Most escaped with their lives, but many were never able to spring free from the trauma of their experiences. Such terrors have endured far beyond the lifespan of the regime.

There is no doubt that many people will find this book a valuable contribution to the history of WWII and beyond. The cover is striking and the content fascinating and exceptional.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments