Author Interview: Nancy Ludmerer

For me, having to show up with work is the most important part... participating in weekly workshops means that even when life intervenes, I produce something.

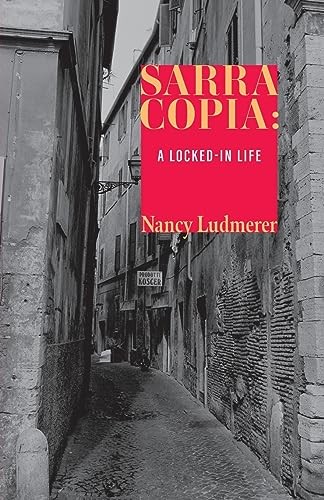

I'm delighted today to welcome author Nancy Ludmerer to my site. Nancy shares insightful information about her new novel Sarra Copia: A Locked-In Life.

On a personal note, thanks Nancy for reaching out. This the first interview I've been able to conduct since war broke out on October 7th. Since then I have been unable to respond to requests for reviews or interviews. I am hoping this interview marks a return to the enjoyment and satisfaction I have always received from discussions with authors. I refer to the quotation I lifted from her interview above "when life intervenes, I produce something."

What inspired you to write this novella?

During most of my writing life, I also practiced law. In 2006, a legal case brought me frequently to Milan and Rome and eventually to Venice, on a weekend when our litigation team went there to relax and sightsee. On Sunday I left my colleagues at brunch at a hotel on the Lido and visited the ancient Jewish cemetery. Although I had been to Venice before and explored the Jewish ghetto, I had never visited the cemetery. It was a hot buggy day and I was the only visitor. The cemetery caretaker helped me find graves of interest and gave me a handout in English about the better-known residents. The only woman mentioned was Sarra Copia.I consider myself reasonably well-versed in Jewish history and culture, but I had never heard of her. The pamphlet described Sarra,

"resting in the cemetery next to her father, who had encouraged her gifts, and her little daughter who had pre-deceased her. With her lively talent and great culture, she was a recognized poetess and conversationalist, as well as the guiding light of a literary salon in her own drawing-room during the first half of the XVIIth century . . .".

Standing beside Sarra's grave, slapping at mosquitoes, I vowed to write about her. Fifteen years later I made good on that promise. Why did it take so long? At the time I first learned about Sarra Copia, and for more than a decade after, I was writing and publishing short stories and flash fiction.I didn't think Sarra's story could be told in 500 or 1000 or even 3000 words. When I retired from the law in mid-2018, I began to focus on longer work.In 2020, I wrote my first historical fiction, a story of around 8000 words, "The Loneliness Cure' (published in Best Spiritual Literature Vol. 7 2022 (Orison Books)), about Hannah Rochel Verbermacher.As a teenager in early 1800's Ukraine, she had the chutzpah to study Torah and Talmud, debate the rabbis, and develop her own following, preaching from her own small shul. Once I completed that story, I wanted to continue to write stories about little-known or unknown Jewish women who had done something remarkable.It was time to tell Sarra's story.

Can you tell us about your writing process?

Three things were critical to my writing process as I embarked on this journey with Sarra.

First, research. I love doing research, even for stories that are not historical fiction.One of my micro fictions (100 words), "Collateral Damage," (included in my collection Collateral Damage: 48 Stories), is told from the perspective of a fly. I researched the lifespan of the average housefly to make sure the story was accurate. For this novella, I immersed myself in books about Venice and its Jews and the two books written in English about Sarra Copia. Both are scholarly works, the first by the late professor Don Harrán of Hebrew University and the second, by Professor Lynn Lara Westwater of George Washington University. Both volumes include English translations of 17th century documents that were pure gold to me in the writing of this book, documents such as Sarra's father's will; Sarra's Manifesto, written in response to being publicly denounced for heresy; and fifty letters written to Sarra by an elderly Catholic poet she never meets (alas, her letters to him did not survive). I obtained permission from the respective publishers to use excerpts of these documents in my book, where I believe they help to create a sense of time and place as well as provide insight into the personalities of key characters.

Second, it was important to me to have time to think (and sometimes dream) about my characters. This doesn't necessarily mean my hand is moving on the keyboard or the page. Rather, I try to immerse myself in a character's internal life and discover what that character notices, thinks, and feels.This was particularly important with Sarra, whom the book follows from childhood to adulthood.

Finally, I need deadlines – whether imposed by a workshop, a writing coach, or a publisher. To keep myself going week-to-week, I have participated for years in a weekly, prompt-based Zoom workshop, led by Beth Ann Bauman. The seven participants submit up to 300 words based on one of nine prompts Beth circulates each week; submissions can be part of a larger work or flash fiction. For me, having to show up with work is the most important part. Obviously, I try to write more than 300 words a week, but participating in these workshops means that even when life intervenes, I produce something.

Shortly after retiring from the law, I began working with Karen Bender, who offered a broader perspective on works-in-progress. Her advice and her support for this project were invaluable. Once again there were deadlines for emailing work to her.

Publishers' submission deadlines also propel my writing process – and this time was no different. I had to submit Sarra Copia:A Locked-in Life by November 14, 2022 for it to be considered in a competition run by the wonderful WTAW Press.I made the deadline and was thrilled when WTAW chose the work for publication.

What roles do fear and anxiety play in the novella?

These emotions are in play but are not as prominent as might be expected from a book set largely in the Jewish ghetto in 17th century Venice. Sarra is forced to live in the ghetto, locked in from sunset to sunrise; she is harassed for being a Jew; and her intellectual achievements are belittled, even at her own salon. In one scene she is accosted by a stranger who hands her a public document, a Discorso, accusing her of heresy, written by a Catholic priest she considered a friend. In another scene her sister Diana comes to Sarra's home in the middle of the night, after a brutal assault. From the book, in Sarra's voice: "Nausea grips me, beyond anything I've experienced since little Rica's death. Silently, I pray to be able to look at my sister, to clasp her in my arms, to comfort her." Sarra battles her way through the anxiety and fear in both incidents. In both cases she responds quickly – writing her fierce Manifesto in response to the friend's betrayal and attending to her sister's care.

What about sadness and melancholia.Do they play a role in the book?

Sarra's baby daughter Rica dies before her first birthday and in one of the saddest and most poignant chapters, Sarra and her family travel by gondola to the Jewish cemetery on the Lido to bury the little girl. Months later, Sarra becomes pregnant again and once more feels hopeful, but she miscarries, nearly dies, and learns she cannot have more children. Sarra's grief is again overwhelming, but she does not become a sad or melancholy person. Ultimately, her resilience and optimism, the legacy of her father's love, return. How do we know? She writes a fan letter to an elderly Catholic poet she will never meet, filled with admiration for his epic poem about the Biblical Esther; her girlish joy when he writes back reflects her spirit and lifts the reader's spirits too. Immediately she writes to the poet again. Now she has something to look forward to.

What moral traits and character attributes may be seen in different characters in the novel?

Three contrasting characters come to mind.

Simon Coppio, Sarra's father. His will from 1606 reveals much about his kindness. He forgets no one in his bequests: the family's two servants, six orphan girls (for whom he leaves dowries), and the poor Jews in the holy land, who will receive an annual donation. Simon's will shows his trust in others, from the Christian notary who has taken down his words; to his wife whom he appoints executor; to his daughters, to whom he leaves whatever funds remain after his wife's death in equal shares with absolute control, with only one caveat – that they remain Jews. He also provides that his daughters are free to marry whomever they please, so long as their mates are upstanding, honest, and honorable.

At times Sarra's father seems so intent on seeing the good in others that he misses their slights. Early in the book he gives Sarra some coins for a ragged little boy singing near the traghetto stop. Ten-year-old Sarra approaches shyly and drops the coins in the boy's cup only to have the boy spit at her. In an instant, Sarra realizes the boy is looking at her father; his venom is intended for him, not for her. Her father doesn't even notice.

Sarra's husband Giacob Sullam. Giacob's main attribute in the novella is his loyalty to Sarra. He does not participate in her salon or inject himself in her correspondence but allows her to pursue these intellectual activities and, when necessary, supports her in them. When Sarra's mother says he should forbid her from hosting the salon, arguing "no good can come of it," Giacob replies, "Sarra's happiness is the greatest good."

Baldassare Bonifacio. There are kind and trustworthy Christians in the book but Bonifacio is not one of them. His overwhelming character trait is his ambition. He is angling to become a bishop and puts aside his friendship with Sarra and attacks her publicly in a widely-disseminated Discorso, even including as evidence a personal New Year's greeting she sent him in response to his own. (As an aside, he does become a bishop, but that is outside the scope of the novella.)

Is there any deeper symbolic meaning to the names of the characters?

Most of the characters in the novella are historical figures and I used their actual names. There are one or two exceptions. In the historical record, Sarra's sister is sometimes identified as Diana and sometimes as Stella. In the book, Sarra's sister longs to leave Venice and the ghetto. Her betrothed is from Mantova and she moves there to live with her new husband. Because Diana was the Roman goddess of the hunt, I chose that name for this young woman rather than Stella; my Diana was hunting for a better, or at least a different, life.

Another character shows up at the very end of the book to whom I give the middle name Dror, which is a Hebrew word with two meanings: a bird (specifically, a swallow) and freedom. I won't say more about that choice of names but you can read about it in the book.

What are you working on now?

I'm reasonably far along in my next book, historical fiction about another largely unknown Jewish woman: Eleanor Marx, the youngest daughter of Karl Marx and the only member of her family who acknowledged her Jewish background. In the 1880's and early 1890's, she was a major force in the labor movement in England and internationally, esteemed by workers from coal miners to shop assistants to onion skinners. She learned Yiddish so she could organize the poor Jewish workers in the East End of London. As a child she was home-schooled by her father and Friedrich Engels; as an adult, in addition to labor organizing, writing tracts, and editing her father's work, she translated Madame Bovary and several Ibsen plays into English and performed (with somewhat less success) on the stage. From infancy she loved cats, and was given the nickname "Tussy" to rhyme with "pussy"; her family and close friends continued to call her Tussy throughout her life. After considering different narrative voices, I've decided that Tussy's cats are best suited to telling her story. The cats, of course, agree.

BIO

Nancy Ludmerer's fiction appears in Kenyon Review, Midstream, New Orleans Review, North American Review, Best Small Fictions 2016 and 2022, Exposition Review, and many other places. Her story "The Loneliness Cure," historical fiction set in early 19th century Ukraine, was awarded Orison Books' Best Spiritual Literature Prize for Fiction in 2021 and appears in Best Spiritual Literature Vol. 7, 2022. Nancy's debut collection, Collateral Damage: 48 Stories (Snake Nation Press), was the 2022 winner of SNP's fiction prize. Sarra Copia: A Locked-in Life (WTAW Press 2023), was a finalist in WTAW's Alcove Chapbook Competition. Nancy practiced law for over 30 years. She lives in NYC with her husband Malcolm and recently-adopted 9-year-old cat Nova. Read more of her work.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments